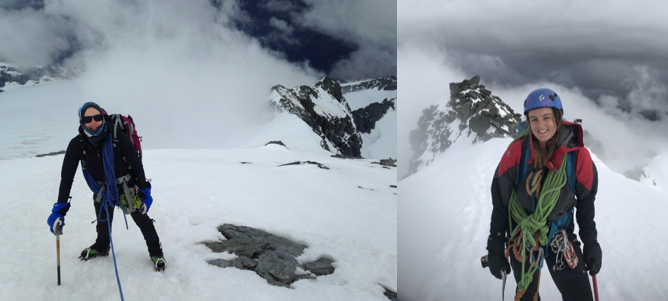

Written by Maria Lastra Cagigas, ft. Jenny, Maria, Henry, Ash – 25/12/2019

It’s 1 am on Christmas day when my alarm clock goes off. Everyone is sleeping at the French Ridge hut, a beautiful alpine hut surrounded by keas at 1480 m elevation in the Mount Aspiring National Park. I think about it for a second: do I really want to do this? I’m lying in the warmth of my sleeping bag, my eyes slowly adjusting to the darkness, and thinking of Mount Aspiring. It’s cold and dark outside and the clouds mask the stars, which means we probably won’t get the best freeze. I know it’ll be a long day. I know there are other less committing and still challenging peaks around, and if we go for Mt Aspiring, we may not make it. But somehow, I feel ready. The challenge is exciting. I tell myself the goal is to come back safe and that gives me enough mental peace to go for it.

From 2 am, the light of our four headtorches moves over rock and snow up to the Quarterdeck Pass, the access to the Bonar Glacier. We rope up for glacier travel before hitting the crevasses and mumble a few words. After a steep snow slope, we reach the top of the Quarterdeck and start descending north. Jenny leads the way. The crampons sink in the snow but it’s early in the night and the temperature is still decreasing, so we hope for a better freeze after 4 am. I’m crossing the Bonar in the silent darkness of the night and thinking of Christmas: thinking of my grandmas’ food and my Spanish friends probably partying right now. I miss them, but I’m happy to be in New Zealand with good friends, doing exactly what I’m doing right now.

With the first light we reach what we think it’s The Ramp, a steep snow slope that gives access to the North West Ridge (III, 2) of Mt Aspiring. Climbing snow is methodical: right axe, left axe, right crampon, left crampon. It’s pretty fun for a while and pretty tyring for a long while.

After reaching the rocky ridge, we change our kiwi coils into mountaineering coils and start climbing. Following the line of less resistance, some exposed moves on rock lead us to the north face, a steep slope covered on snow with a dangerous runout. Using 4 points of contact, Jenny starts traversing it followed by Ash, me and Henry. Although early in the morning, the snow is soft, so we all realise we are in no-fall zone. We are soloing and I’m in tension. Why does the guidebook mention the danger of The Ramp but nothing about this traverse, which clearly has more fatal consequences? I feel we are off-route.

A couple of hours later we reach the North West Ridge again on a snow saddle. We were off route but back on it now, and the next section looks less exposed. The first pair starts climbing up the snowed ridge and we follow them in the distance. Climbing feels good, there is no wind and it’s warm, so we keep moving up getting closer to the summit, hidden by the clouds in the distance.

The clouds have been growing all morning, slowly covering the landscape. We know a whiteout may not take long to come. The ridge slowly narrows and steepens up, so we go back to 4 points of contact. There are cornices on our right and left so we keep climbing up carefully, knowing that the runout isn’t long enough to self-arrest a fall. Around 10 am it starts to snow. The clouds cover Jenny and Ash, so we lose them ahead in the distance. We keep climbing and the precipitation gets heavier, the wet snowflakes make the mountain slippery and the visibility is down to a few meters. I doubt. The snow is soft and getting wet and the ice axes don’t grip properly. A slip would probably mean death. If we go back now, we could reach the rocky ridge before the weather worsens so we don’t get stuck overnight in Mt Aspiring in a storm. We know there is a front coming the next day. The summit isn’t too far though, so we decide to keep going. I hope Jenny and Ash are okay up there, they may be close to the summit by now.

We keep climbing. I can roughly recognise the rocks under the cornice on our RHS from all my previous staring at Mt Aspiring pictures. There is a steep snow climb left and the summit ridge, although we cannot see them. We’ve been climbing for around 9 hrs without stopping and I’m tired, but we want to get to the summit. Jeffrey knows I’m ambitious sometimes. However, the weather gets worse. The precipitation makes the thin fragile ice covering the snow get wet. How much is a summit worth a slip? The next call breaks the heart of any mountaineer but it’s a simple one to make: ambition aside, it’s safer for us to turn around now and come back in better weather with more experience. The difficult part isn’t necessarily to reach the summit, especially when we’re close, but to downclimb over 1000 m elevation of mixed terrain in late afternoon conditions safely. We both agree and start downclimbing.

The storm keeps bringing fresh snow and low vis by the time we reach the snow saddle. We decide to wait for Jenny and Ash to check they are okay while we dig a snow wall to protect us from the elements. In my opinion, part of learning mountaineering is learning to check on your friends because you’re likely their fastest option for rescue should they need it. Around an hour later, their figures appear through the clouds downclimbing the mountain. Relief. They made it to the summit! What a sick achievement so I’m very happy for them.

The weather slightly improves and it’s good enough to keep going, so we leave our snow wall and start downclimbing the now rocky North West Ridge. A few hours and a couple of abseils later we reach The Kangaroo Point, a steep snow slope that connects the ridge to the Bonar glacier. There is two downclimbing options: down the Kangaroo, which is more straightforward but steep and has afternoon-quality snow, or down the rocky buttress, which is much longer and exposed but avoids steep snow slopes. We split, the first pair takes the first option, we take the second.

6 abseils in poor quality rock and several hours of really exposed free solo downclimbing later, we reach the end of the buttress. Although cloudy, at some point the sun has warmed the snow so much that I slip towards a crevasse, sinking completely in the snow. Carefully using the ices axes and a bit scared, I get out and we keep going. Decision-making is the protagonist during the descend: should we traverse that soft snow or stick to the loose and now wet rocks, should we downclimb or abseil, should we go towards the glacier on the north face or stay high?

Eventually, Colin Todd hut appears in the distance. I’m so happy. After all the exposure and sketchy rock and snow it seems we won’t die today, so I’m glad of the decisions we made through the day. We get to Colin Todd hut past 8 pm after more than 18 hrs of climbing. Jenny and Ash follow a different route, so they get to French Ridge hut around 7 pm. We plan to rest and sleep for a few hours in Colin Todd hut and cross the Bonar glacier in the morning to reunite with them in French Ridge hut since all our sleeping and cooking gear is there.

The next morning, I wake up around 4 am and my eyes feel watery. In the dark I reach for my headtorch, but I cannot see the light. I cannot see my hands or where I am. My eyes burn painfully and I slowly realise I didn’t wear my sunglasses enough so I have snow blindness. I wake Henry up. I can’t see a thing and there is no one in the hut. I can hear a storm outside. We are stuck in Colin Todd hut for the next 2 days, waiting for my sunburnt eyes to recover enough vision to cross the glacier back to French Ridge.

To our luck, Kim and Aritza, experienced mountain guides from Tasmania and Spain, arrive in the hut to climb Mt Aspiring. They hear our story and share dinner, a warm drink, medicines and good conversation with us. Aritza, who used to spend his summers in my hometown in northern Spain (small world!), tells amazing stories of his guiding in Cordillera Blanca in Peru. Kim, member of the NZ Alpine Team, teaches us about pitching, simul and solo climbing when in the mountains. We learn the mountaineering community is a small and caring one.

The 28th of December my eyes are recovered, the morning is clear, so we can finally head back. The snow sparkles in the Bonar and we climb a small peak on the way to admire the views. It’s stunning. A few hours later, downclimbing the Quarterdeck Pass feels like being at home.

Back at the French Ridge hut, we “reunite” with the NZ crew. Or so was the plan, until we find the NZ crew’s love letter at the radio station.

We pack and hike down to the valley. On the way down, we half joke about being abandoned in the mountains. “We’re happy if you’re happy”. OMG. We arrive in Mt Aspiring hut after another 12+ hr day and I’m grateful. It’s been such an adventure and such a learning experience. There is so much room for improvement and so much psyche to improve. And overall, so much love for the mountains!